6MO: Breakthrough Music Report

Chartmetric Music Industry Trends | H1 2022

January 1 - June 30 | 2022

Welcome to the seventh edition of 6MO, our semi-annual report on music industry trends (if you're looking for music trends from H2 2021 and earlier, click here).

Part 1: Find who blew up in the first half of 2022 (H1 2022, January 1-June 30) to get a sense of the future of the music business, and uncover the world’s breakthrough artists and tracks on music streaming platforms and social media.

Part 2: This edition we focus on our special deep dive, “Redefining Catalog: Same As It Ever Was?”

Feel free to share the animated infographics, tag us on social media (@chartmetric), and join us at 11:30 a.m. ET on Wednesday, Aug. 3, for our special Off the Charts livestream, where we'll be discussing the whole report and answering all of your questions.

Share the animated infographics and tag us on social media (@chartmetric), and enjoy the latest important music industry trends and statistics!

Breakthrough Artists by Chartmetric Artist Score Gain

With several different levels available within Chartmetric’s Career Stages, finding breakthrough artists to watch in the immediate future gets interesting. For Legendary stage artists (having releases > 30 years ago), US singer-songwriter Kenny Loggins rode the fighter jet slipstream of Tom Cruise’s Top Gun: Maverick reprise, which came out in May. Loggins’ 1986 hit “Danger Zone” remained untouched in the movie sequel, giving Loggins a 98 percent Chartmetric Score increase to 56K. Our Superstar tier featured an unfortunate No. 1, as Indian rapper Sidhu Moose Wala was murdered in May. His fans all over the world remembered him through his music, increasing the artist’s score 348 percent to 273K. The biggest Mainstream tier rise came via British Art Pop star Kate Bush and her track “Running Up That Hill,” which lit up the digital platforms once its diegetic sync in Netflix show Stranger Things premiered in May.

Breakthrough Artists to Watch on YouTube

Hopefully their name is an indication of future success, because French Electro rockers Supermassive blew up on YouTube in 2022. Starting at 1.2M channel views on Jan. 1, 2022, the duo saw incredibly consistent growth, ending June 2022 with almost 600M views. That 48K percent increase landed them in the No. 1 spot for artists to watch on YouTube in 2022. Arguably the most interesting story of this Top 10 list is the bottom half, all of whom had TikTok to thank for catapulting their YouTube channel view growth (and ultimately, their careers). In the past, we’ve written about how good TikTok has become for helping tracks go viral, but now, it looks like artists are finding a way to utilize TikTok to build their brand. Iranian American singer Em Beihold, British-Australian R&B artist OXLEE, Nashville Country singer-songwriter Thomas Mac, British-Gambian rapper Jnr Choi (who first went viral on TikTok with “To the Moon”), and Louisville, Illinois, Country artist Bailey Zimmerman are all making TikTok work for them, building off-platform success and rounding out the Top 10 artists to watch on YouTube this year.

Breakthrough Artists to Watch on Wikipedia

Death, unfortunately, continues to be a significant event that garners public attention. Seven of this Top 10 passed away in the first half of 2022, either as a result of old age, due to unclear circumstances, or even, in the case of beloved Indian rapper Sidhu Moose Wala, due to assassination. Television was the other major driver for public notice: 2019 breakout star Alexa Demie shot to fame again thanks to the 2022 release of Season 2 of Euphoria, while wrestler-musician Elias’ controversial return to WWE TV as his own younger brother “Ezekiel” piqued new interest in his character.

Breakthrough Artists to Watch on Twitter

During January 2022, the end of the seven-month Twitter ban in Nigeria reignited fan engagement with musical artists, yielding three of the Top 10 Twitter gainers from the sub-Saharan country. Maybe unsurprisingly, there are no US artists who made it to Top 10, a trend we've seen over the past two years. This could be an indication of Twitter becoming more critical for international artists to grow their global audience, similar to Facebook.

At No. 1, is influential Nigerian artist and activist Yemi Alade. Thanks to her versatility in different languages, both her musical achievement and engagement in charity and advocacy programs are widely acclaimed globally. In 2020, Alade was appointed a Goodwill Ambassador by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

Nigerian artist Rema (No. 8) started his musical career after posting a viral freestyle video on Instagram. His track “Calm Down” charted on multiple streaming platforms and generated thousands of posts on TikTok.

Unsurprisingly, K-Pop groups once again showed the world how strong the K-Pop community is. TREASURE (No. 4), aespa (No. 5), and ENHYPEN (No. 7) have remained in the Top 10 since 2021 and constantly grow new followers with consistently engaging content.

Karol G (No. 2) is one of the most streamed Latin artists on Spotify and her latest single “MAMIII,” a collaboration with Becky G, charted No. 1 on streaming platforms and on Billboard in multiple countries.

Breakthrough Artists to Watch on Spotify

If there’s one thing that this period’s breakout artists have in common, it’s TikTok. Both our No. 2 spot (Nicky Youre) and No. 4 spot (Dazy) gained 13M+ Monthly Listeners thanks to the viral success of their track “Sunroof”, earning 960 and 870 percent increases, respectively. Pailita (No. 5) and Polimá Westcoast (No.7) also gained around 14M Monthly Listeners due to their hit collab track “ULTRA SOLO,” which has been featured in 2.8M TikTok videos since its release. Even our frontrunner Kate Bush (No. 1), whose song exploded thanks to Netflix’s Stranger Things, found even more social resonance through TikTok, and gained even greater exposure thanks to both platforms. Sitting at a total of 40.6M Monthly Listeners, Kate Bush certainly remains this season’s most impressive Spotify riser.

Breakthrough Artists to Watch on Instagram

At the No. 1 spot for artists to watch on Instagram in 2022, trans Brazilian singer and TV personality Linn da Quebrada comes in at a comfortable 906 percent growth rate. Starting the year at around 316K Instagram followers, by the end of June 2022, Quebrada had amassed almost 3.2M — a tenfold increase. And when it comes to non-American artists topping our list of 10 artists to watch on Instagram in 2022, she’s not alone. Two other Brazilians, three Indian singers, a Congolese legend, and a Eurovision-winning Ukrainian Rap group make for a list so global that we’re used to only seeing it on YouTube.

Breakthrough Tracks to Watch on Shazam

The correlation between TikTok and Shazam appears to be stronger than ever. Eight out of this Top 10 were boosted thanks to challenges, dances, and general popularity on TikTok. While Rnbstylerz’ “Like Wooh Wooh” and Katy Perry and Alesso’s “When I’m Gone” trended globally, BL Zero, Dj Karri, Lebzito and Prime De 1st’s “Trigger,” Ryan Castro’s “Mujeriego,” and Mark Neve’s remix of bryska’s “odbicie” went viral in South Africa, Mexico, and Poland, respectively. DJ Wady, Sean Finn, and MoonDark’s 2020 House beat “Pasilda - Sean Finn Sundown Radio Edit” and Sinéad O’Connor’s 1987 track “Drink Before the War” were the only two anomalies. The former found its revival this summer in Hungary, and the latter got its second wind thanks to a sync with an emotionally charged scene in Season 2, Episode 4 of HBO’s Euphoria.

Breakthrough Tracks to Watch on TikTok

The No. 1 TikTok track was not labeled as such (one of TikTok’s biggest metadata issues), but Don Toliver’s “No Idea” (originally released May 2019 and part of the slowed + reverb music trend), had another clip of the atmospheric R&B track uploaded. This time around, it gathered 1.8M TikTok uploads along the way. The “official” version of it has 4.2M videos to date, but “No Idea” presents one of the best and most challenging parts of the platform: how to track all the user-uploaded audio and know when your song is being used.

Egyptian actor Karim Mahmoud Abdelaziz is credited with the No. 2 song “Al-Ghazala Ray’aa” as promotion for his January film release of Men Agl Zeko, and the No. 5 track saw one of the most refreshing celebrity moments: country viral sensation Mason Ramsey revealing he’s happy working at a local Subway restaurant, to the tune of his 2019 release “Before I Knew It.”

Breakthrough Tracks to Watch on Pandora

Pandora, the US-only streaming platform, continues to be a different path to popularity outside of the TikTok and Spotify paradigm. Nashville-born band Old Dominion takes the No. 1 spot with its feel-good track “No Hard Feelings” growing 827 percent to 23M+ streams. Without significant help from playlists, the track began pinging top Shazam charts in cities across the US and Canada, and by mid-April, US radio stations roughly doubled its amount of spins. Within a month, Pandora daily streams increased to 150K+.

The No. 3 Pop Country track “Wishful Drinking” from Ingrid Andress and Sam Hunt saw a similar trajectory, while the No. 2 track’s success comes from a known hit-maker, Netflix. Arcane: League of Legends launched late last year, but the title track “Enemy (with JID)” slowly climbed up Pandora’s algorithms for an 824 percent increase to 23M+ streams.

Special Report - Redefining Catalog: Same As It Ever Was?

Back in 2018, we first wrote about the concept of “frontline” and “catalog” music, in the context of a new feature we were providing in the Chartmetric app:

"In the recorded music business, ‘frontline’ has traditionally been considered any track less than 18 months old. ‘Catalog’ was any music older than that 18 month period. This distinction — while mostly arbitrary to everyday fans — meant a lot to how money was allocated to a recording artist’s career."

According to former Spotify Chief Economist Will Page, the distinction was largely an era-specific byproduct of charting rules:

"Back in 1991, the industry was going through a format change; consumers were replacing their vinyl collections with CDs. As a consequence, purchasing albums for the second time became the norm — none more so than Meat Loaf’s classic Bat Out of Hell (1977). This second wave of demand caused this 14-year-old album to dominate the charts — again! Yet the purpose of charts is to promote new releases, not old, so in response the ‘catalogue rule’ [in many countries] was born — decreeing that only ‘new’ or ‘frontline’ albums were chart-eligible, while anything released more than 18 months ago was ineligible. The rule succeeded in removing Meat Loaf from the top of the charts — and all because the music industry was struggling to deal with a format change."

Two decades later, the music industry was saved from the mp3 era by another disruptive format change, and digital streaming platforms quickly focused on growing their respective subscriber markets with their extensive catalogs, eventually making new songs a less important aspect of how society consumed music. Algorithms would feed less new releases to passive listeners, and more “new-to-them” music from catalog.

While streaming made access to older records nearly universal, it wasn’t until TikTok arrived on the world stage in 2018 that the industry, in many countries, realized they could market catalog like they did frontline. Sure, old songs had always been available to users on Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube, etc., but as many have said before, it was an attention economy. TikTok controlled attention, en masse, and now to the tune of 1 billion monthly active users.

Around the same time, a second, more behind-the-scenes force fueled the hunger for old music: Wall Street- and private equity-backed song rights, IP management, and royalty fund companies like Hipgnosis, Reservoir, Tempo, Primary Wave, and Round Hill Music. Without the need to house a stable of songwriters nor unproven songs, these companies bought their composition assets after they had shown their market power, and paid those songwriters handsomely, while the companies marketed their songs like a frontline label would. It’s changing the face of publishing, and the Hipgnosis philosophy of seeing songs as recession-proof, steadily growing financial assets has brought the kind of funding to old music it’s never seen before. Catalog music now thrives in a digital environment where an old Fleetwood Mac or Kate Bush song getting thrust back into the limelight is an ostensibly regular occurrence.

Where is listening attention really going?

Now that the music industry is well aware that catalog can be just as trend-worthy as frontline, it’s worth examining whether the 18-month window is really all that informative anymore. Luminate recently published a study claiming that catalog streaming consumption is up 19 percent in 2022, and frontline streaming consumption is down 2.6 percent; however, the lion’s share of that catalog consumption happened between 2017 and 2019 — technically a different decade, but not really that old at all. In other words, it might not make much sense anymore to lump in Taylor Swift tracks with Harry Belafonte tracks if the Taylor Swift tracks are still far more relevant (though technically catalog under the 18-month definition). Maybe, as Will Page argues, we just need to widen the frontline window a bit.

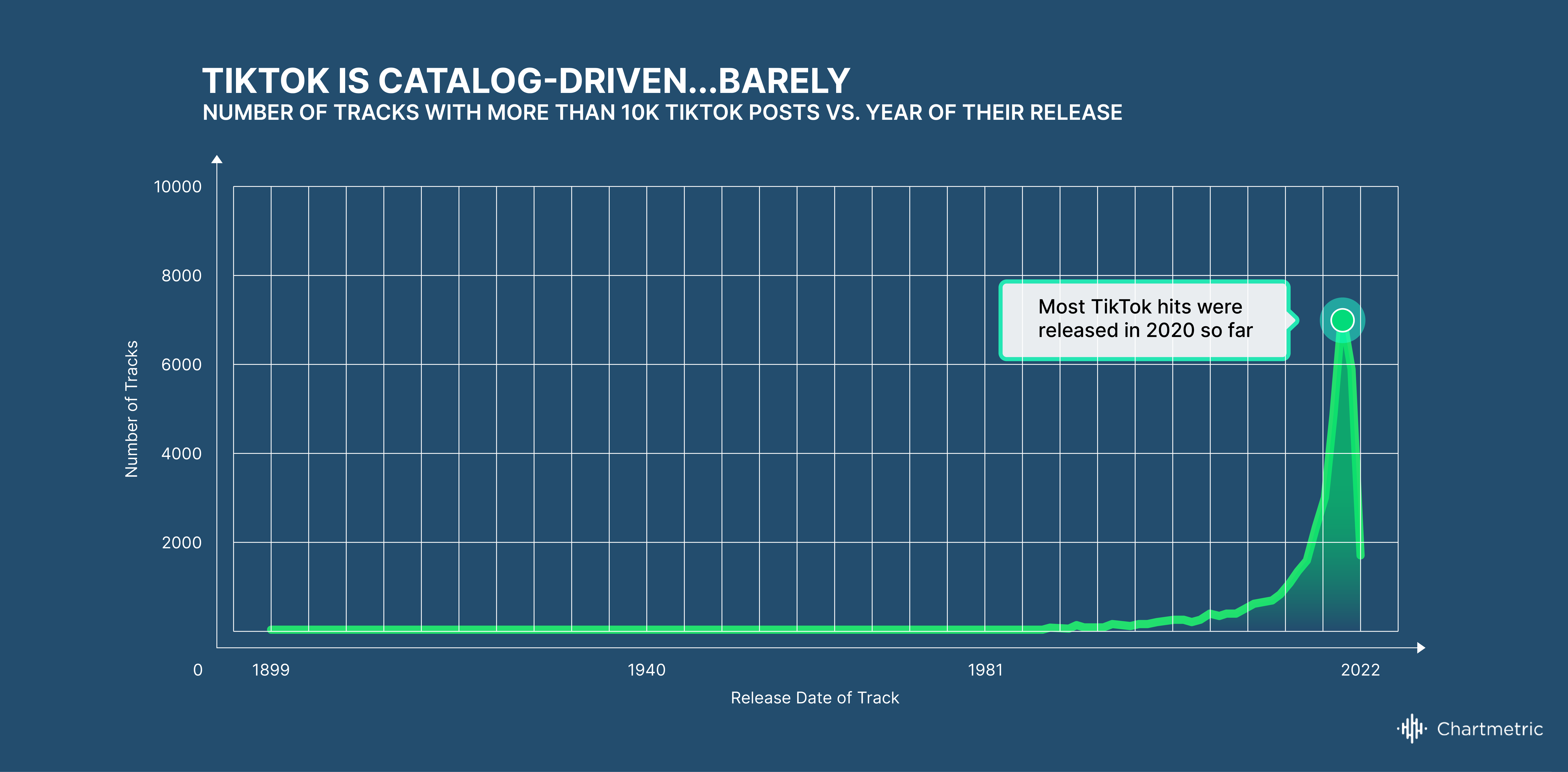

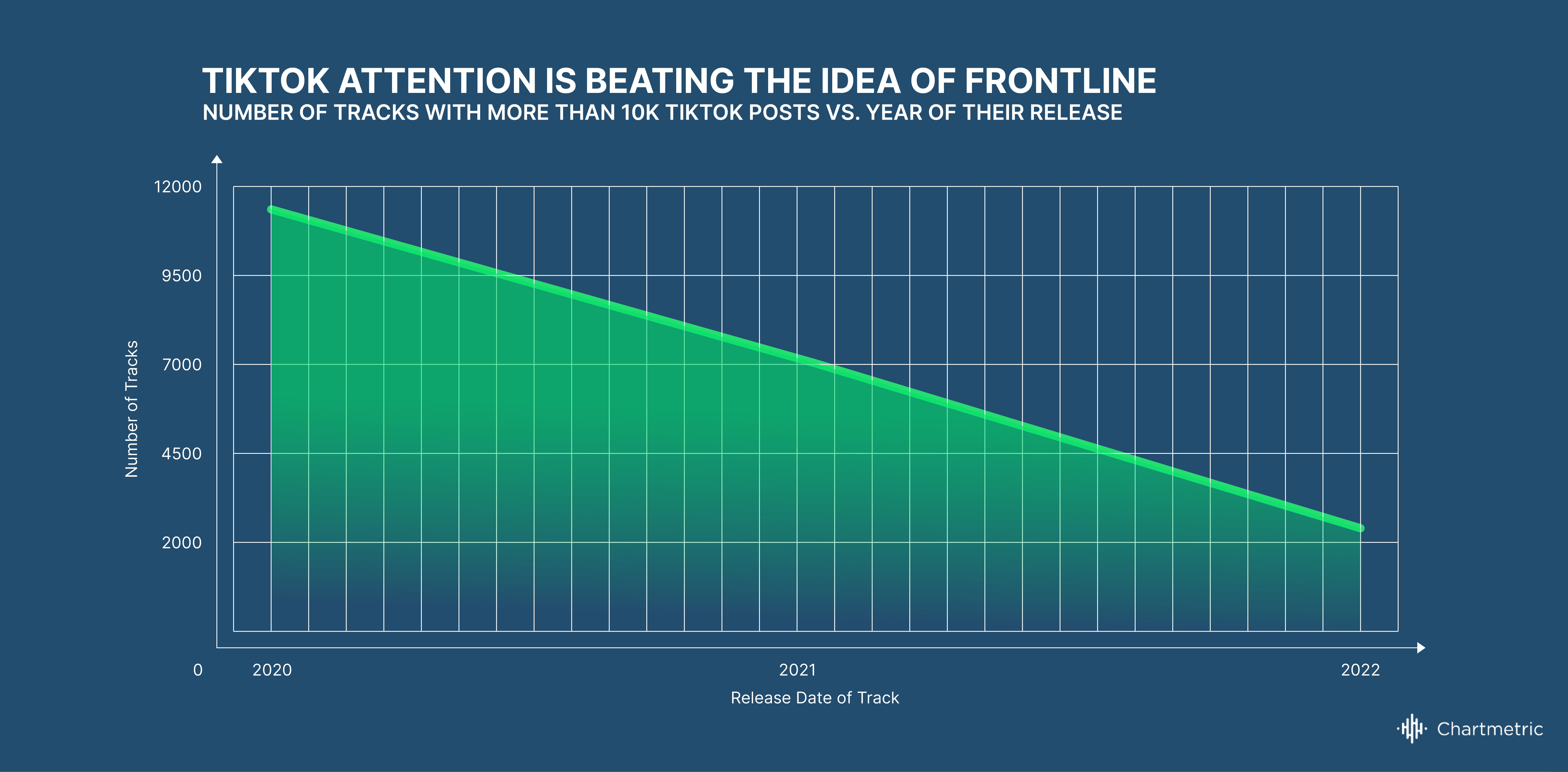

To examine whether the 18-month definition has any merit today or if it just ends up misleading the music industry into thinking that really old tracks are blowing up all over the place, we started with the universally accepted view that TikTok has been the primary platform for generating viral hits — and for helping to drive an increase in catalog consumption — in the last four years. Operating on that assumption, we charted every track in our database that has received more than 10K TikTok posts against the release dates of those tracks.* Here’s what we found.

Catalog Insight 1: In general, the tracks that generated the highest volume of activity on TikTok were probably released more recently than you think, despite the numerous throwback stories we've been reading about lately. In fact, the bulk of the tracks that got significant traction on TikTok were released in the last five years, which aligns with Luminate’s findings that tracks released between 2017 and 2019 saw the biggest growth in consumption under the traditional definition of catalog.

For tracks released before the 2010s, however, there really wasn’t much activity happening at all, and the one-off pre-2010s sensations (Kate Bush, Fleetwood Mac, etc.) we hear about in the press are really more the exception and not the rule. Maybe the real trend is not that catalog is blowing up, but that our definition of catalog is outdated, and we should consider widening the window from 18 months to anywhere from 3-5 years. This aligns with Will Page’s timeframe (36 months) of the new catalog streaming definition mirroring the share of demand by traditional sales.

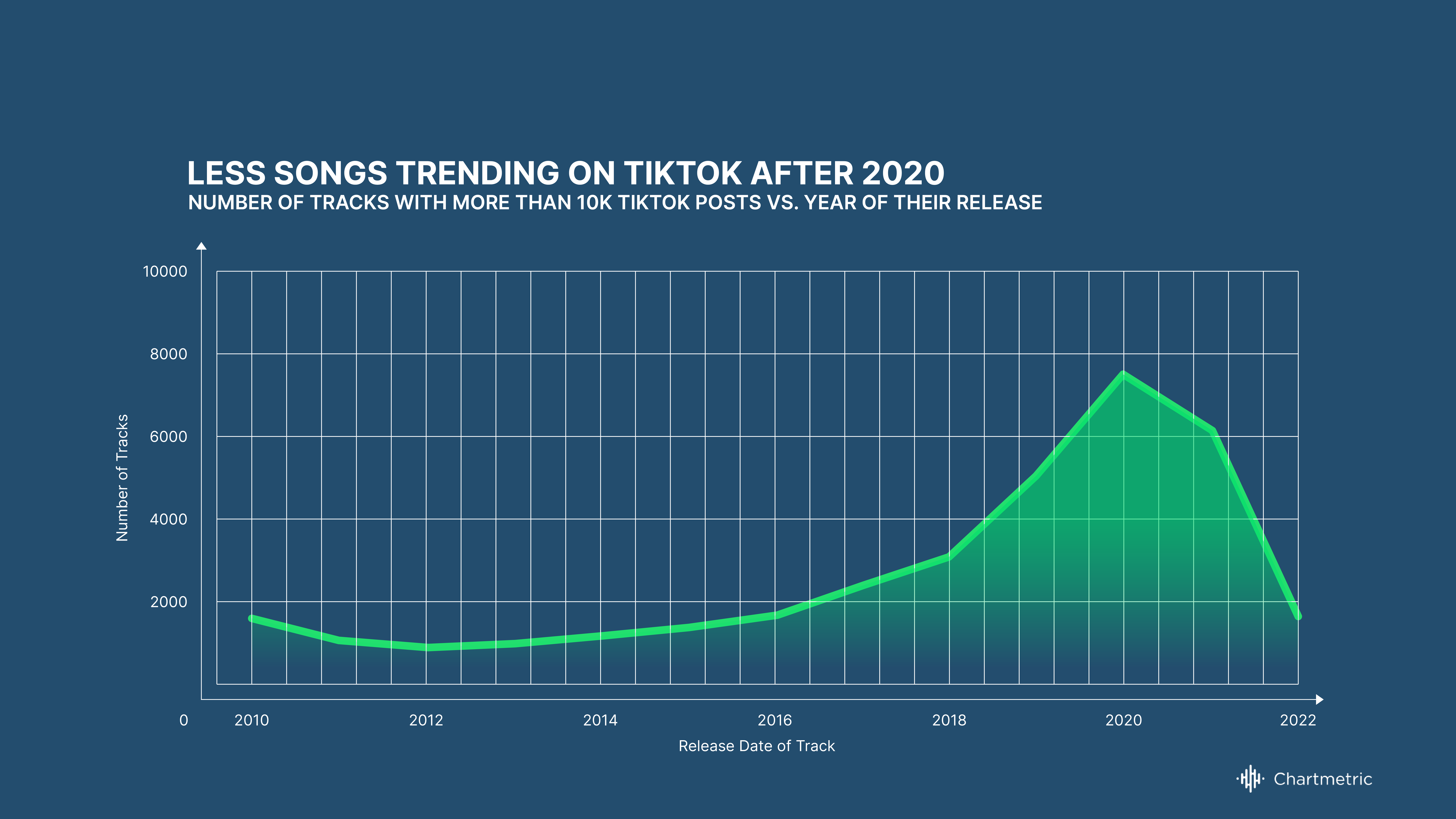

Catalog Insight 2: There was a dramatic peak in the diversity of tracks released in 2020 that generated TikTok activity, but in the subsequent year and a half, that diversity narrowed. There are a number of possible explanations for this trend, all of which are likely interrelated and none of which is mutually exclusive.

- Pandemic lockdowns accelerated the adoption of TikTok by independent music creators in 2020.

- Tracks from two years ago tend to be the most popular on TikTok.

- TikTok was still available in India (tied with China at 1.4 billion people as the most populous country in the world) for the first half of 2020.

- Big music companies caught on to the power of TikTok and have now started to consolidate the market power of their priority tracks on TikTok, which may account for the decreasing number (so far) of unique post-2020 tracks generating TikTok activity.

Because virtually any track is available to any music consumer irrespective of release date, we’ll likely continue to see more pre-2010s releases get their second chance at capturing the limelight, but in the grand scheme of things, these instances are likely to remain outliers. The more rule-defining trend is the widening timeline of what’s capturing the bulk of music consumer attention, i.e., within the last five years (market-driven) instead of within the last year and a half (traditional frontline). Of course, what captures attention on TikTok doesn’t always translate to consumption on streaming platforms, but it’s certainly an important digital signal of where to focus your resources to maximize engagement for your music.

Pay attention to what makes attention pay

Relying solely on an internally-focused, time-based system, especially one as narrow in scope as before and after 18 months, is somewhat shortsighted when deciding where to allocate music marketing budgets. An attention-based system is becoming increasingly important and can help answer two important questions:

- On which songs should I focus my attention?

- What digital signals indicate spikes in audience attention?

Collecting data from more than 25 streaming and social media platforms, we are in a position to measure the resonance of songs at a global level, and in as much a comprehensive way as possible. In our experience, there are more signals than just TikTok posts that correlate with surging music on its way up, such as global Shazams.

Let’s examine the tracks that have charted on Spotify and YouTube since 2020, and attempt to show how the old notions of frontline are becoming less relevant. New forms of attention can point to where to focus resources, and with a little luck, earn a high upside in royalties on the backend.

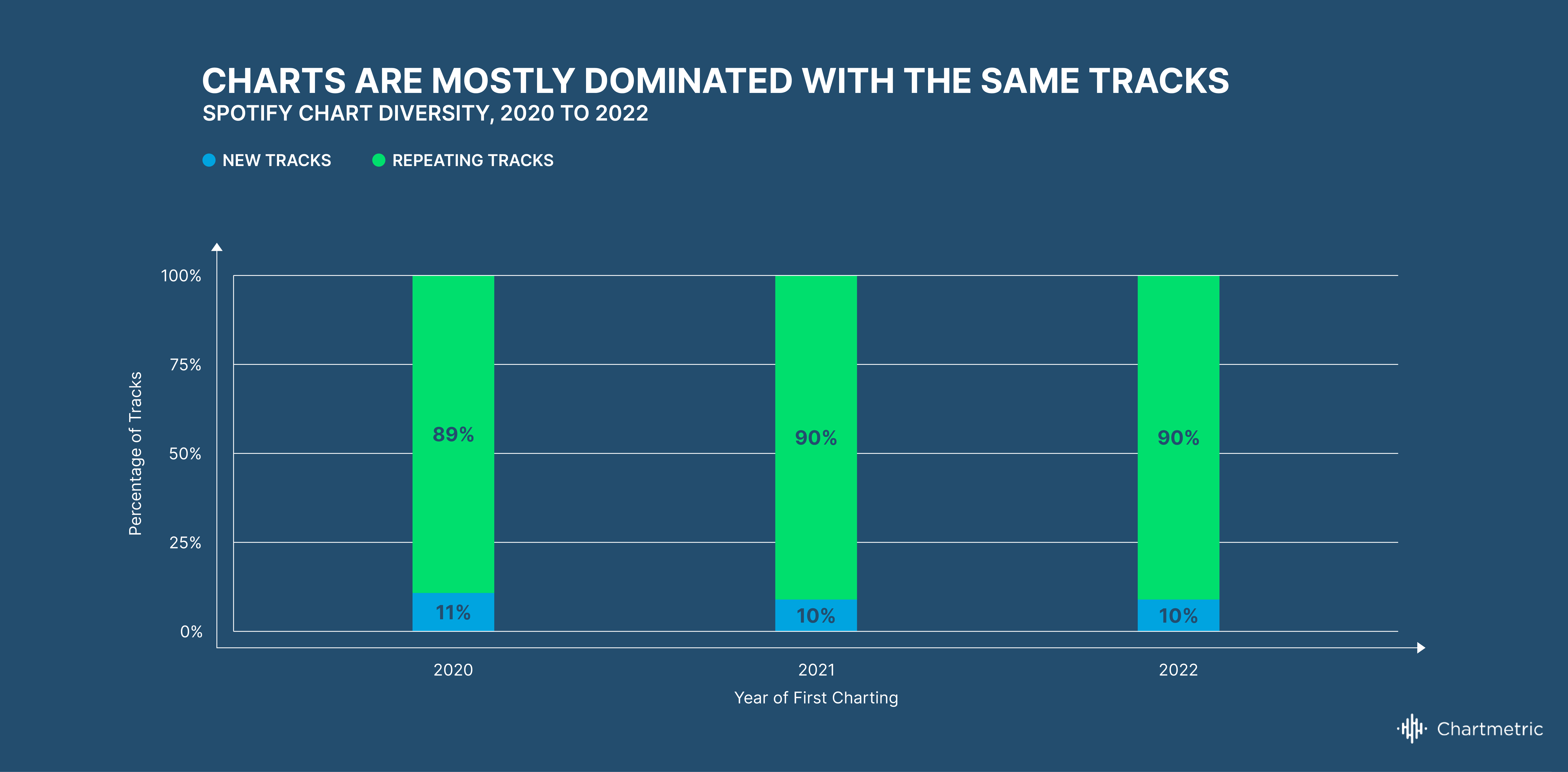

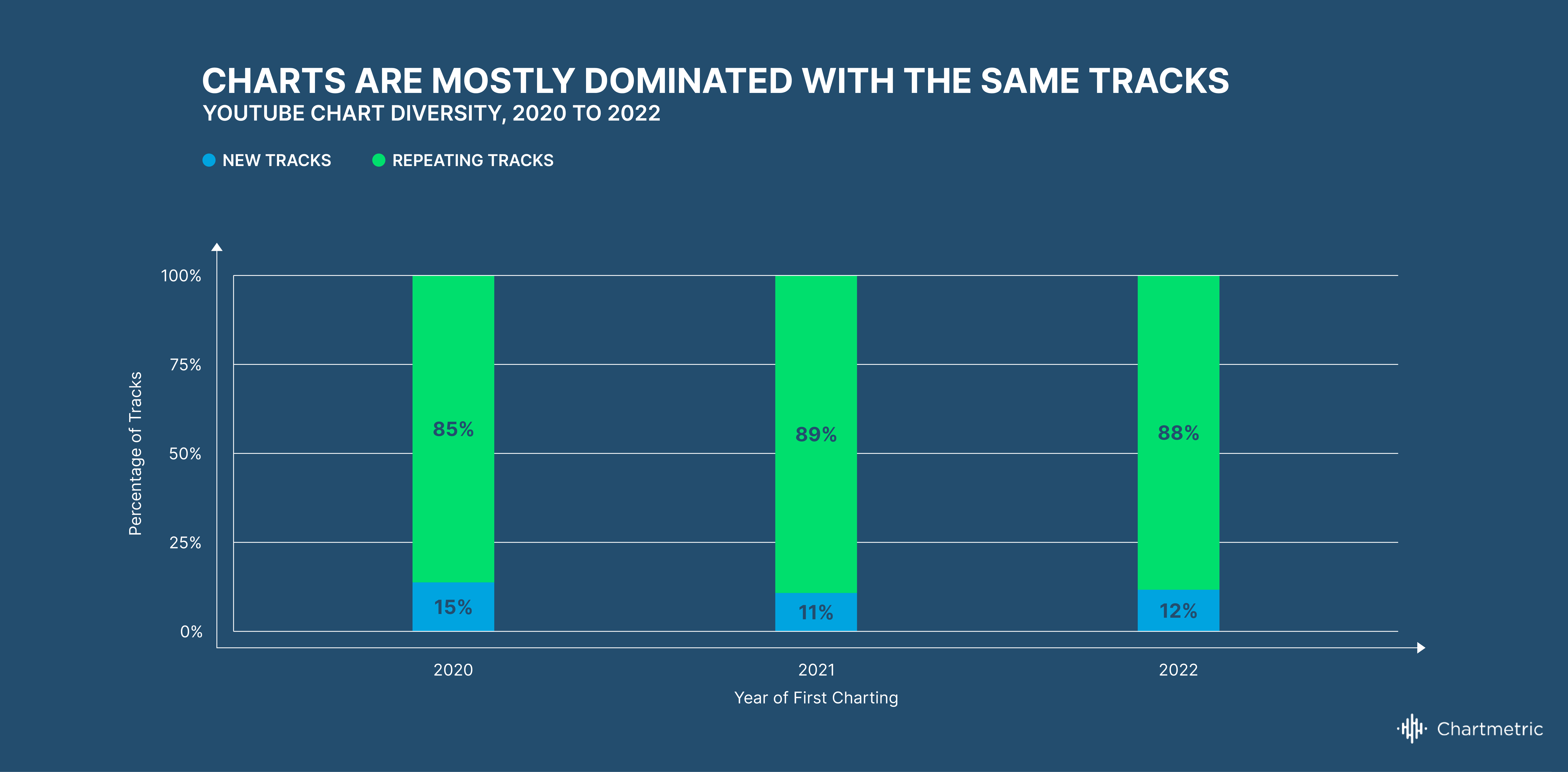

Attention Insight 1: On major streaming platforms, the charts don’t really change much. Roughly 90 percent of the tracks that chart on Spotify and YouTube stay there year after year. That leaves just 10 percent of the real estate for new tracks to make it big on those platforms. Could the narrowing of the diversity of TikTok tracks getting more than 10K posts be a sign that TikTok is soon to follow in Spotify and YouTube’s footsteps?

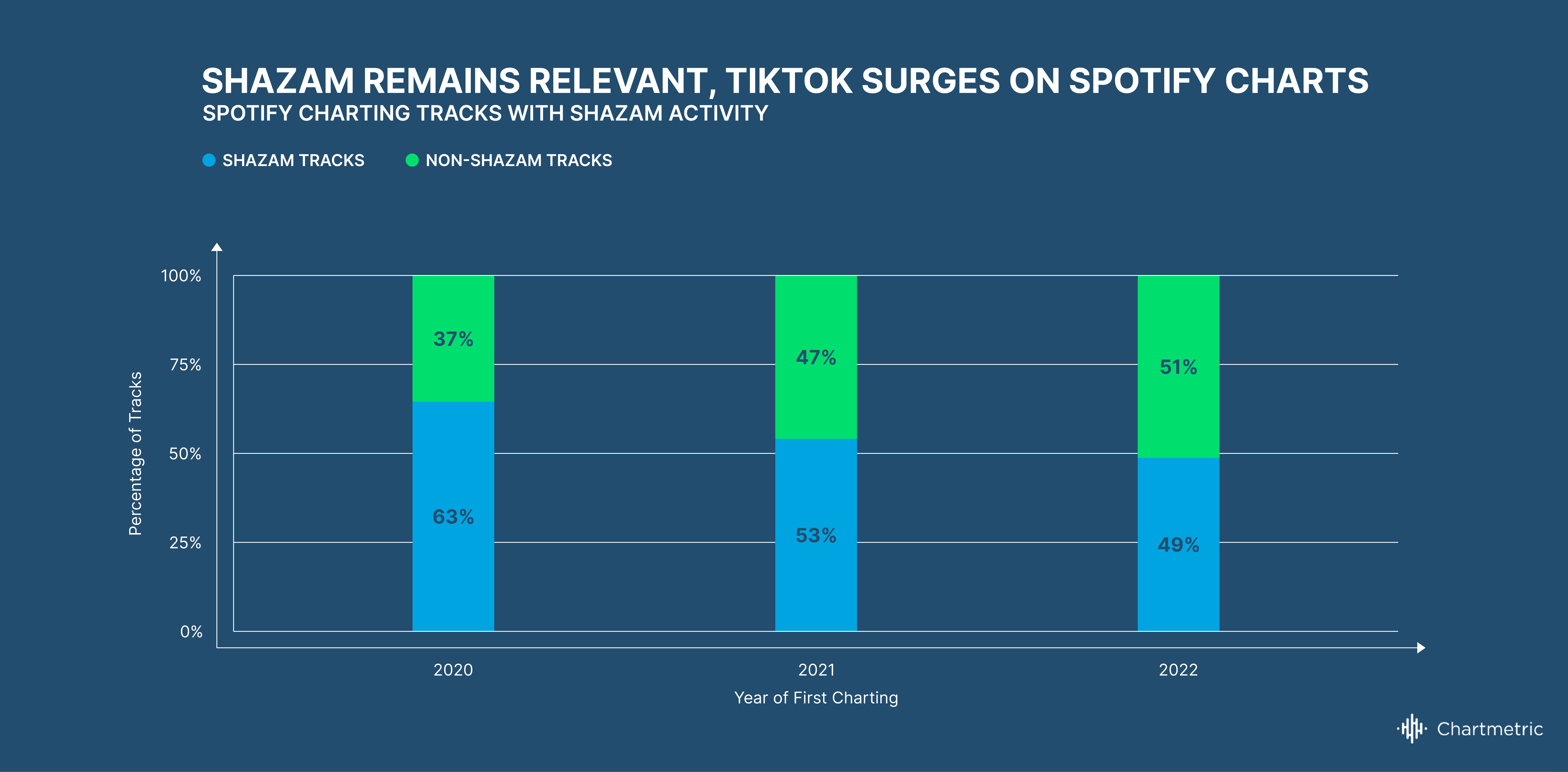

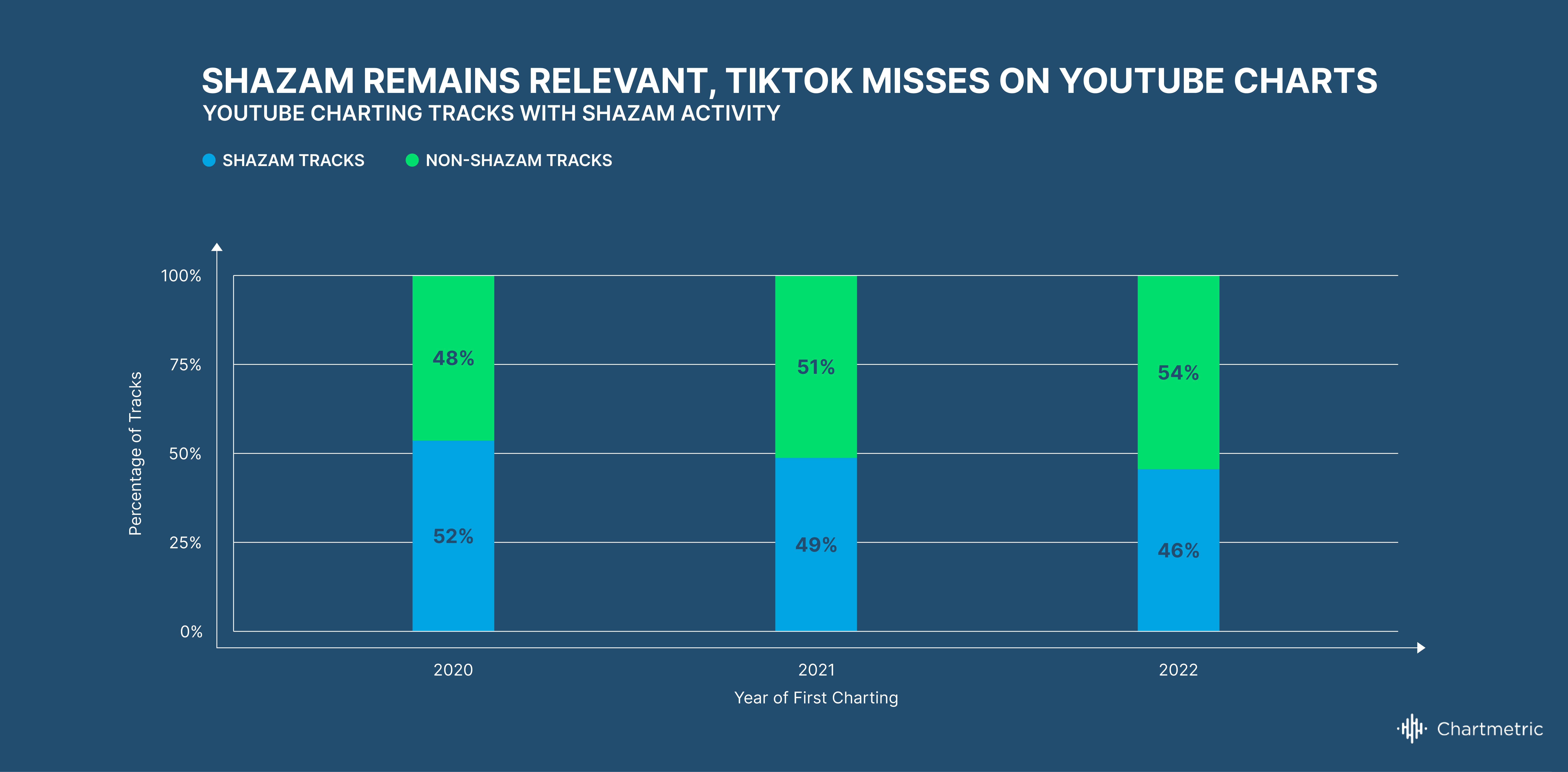

Attention Insight 2: Significant Shazam activity (>10K global Shazams, by the date of first charting) are actually the highest correlated with Spotify and YouTube chart appearances (around 50 percent); however for Spotify, that correlation appears to have declined from 63 percent to 50 percent from 2020 to 2022. For example, 713 of the 1,138 unique tracks (63 percent) that charted on Spotify in 2020 had significant Shazam activity, as defined above. That percentage seems to be declining, if only slightly.

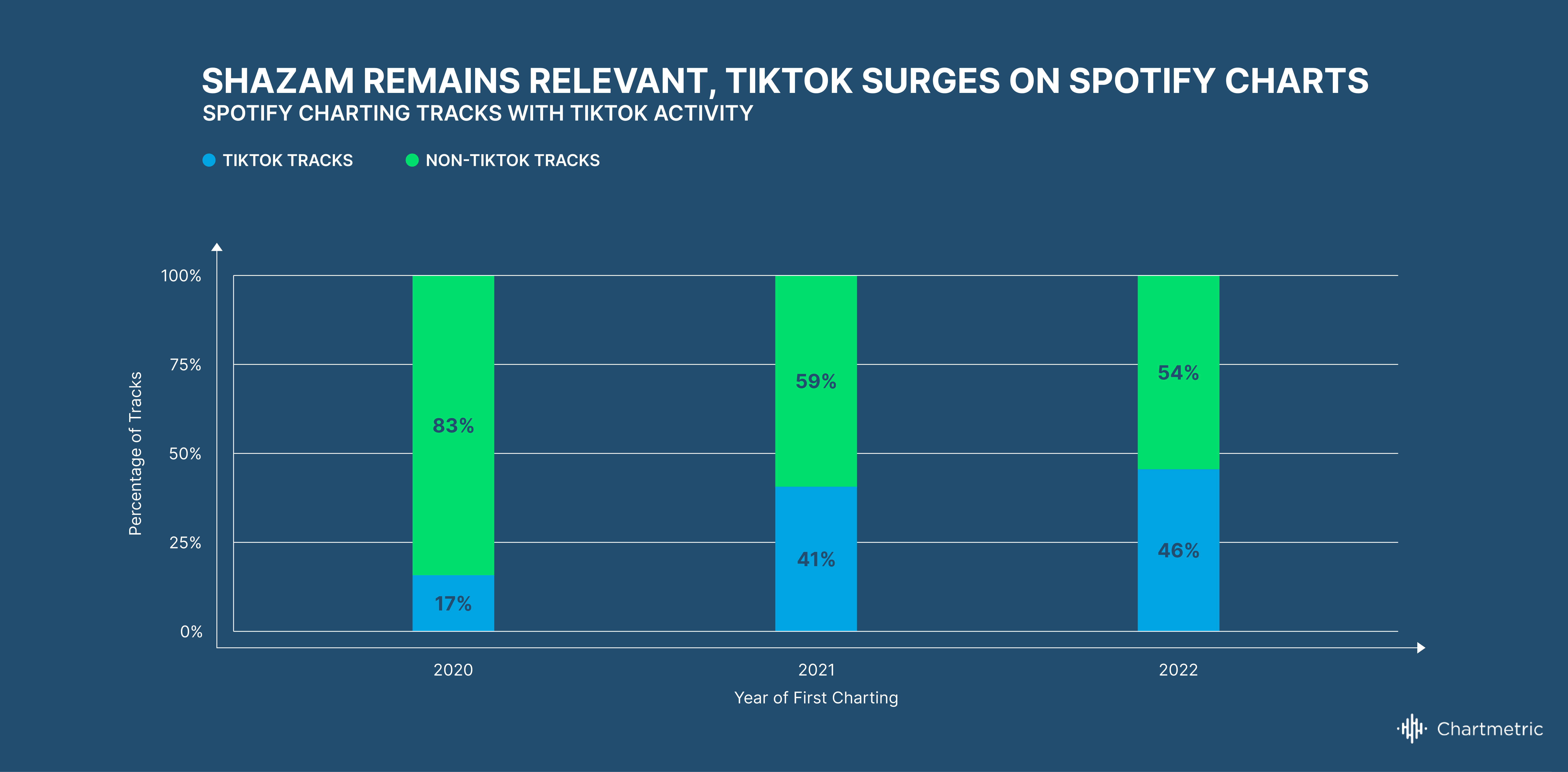

TikTok posts are the second highest correlated with Spotify chart appearances (approaching 50 percent in 2022), and that TikTok-Spotify correlation jumped dramatically from 17 percent to 40 percent from 2020 to 2021. As an example here, only 195 of the same 1,138 unique charting tracks (17 percent) had concurrent TikTok success (>10K TikTok posts) in 2020. The following year, 425 of the 1,043 charting tracks (40 percent) were associated with the same TikTok success.

So, either pandemic lockdowns meant more people were Shazam’ing tracks from their favorite video streaming series, or Shazam became slightly less relevant as a standalone music discovery platform, as TikTok relevance increased dramatically.

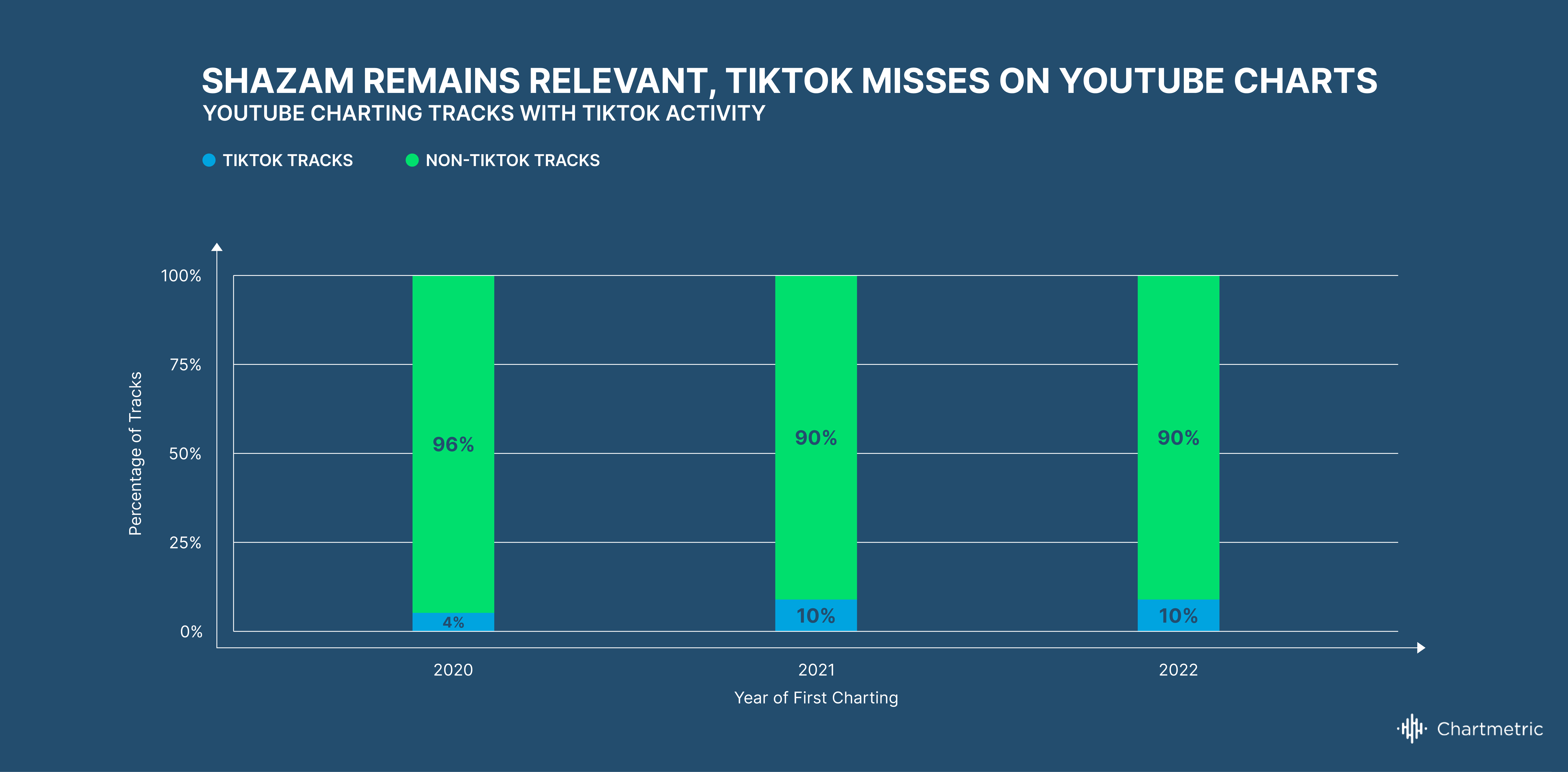

For YouTube charts, TikTok seems to be a non-factor. Since 2020, the amount of YouTube charting tracks with concurrent TikTok success hovered in the 5-10 percent range. For example, only 62 of the 600 unique charting tracks (10 percent) on YouTube had our definition of concurrent TikTok success in 2021. This suggests little relationship between the TikTok and YouTube consumption worlds, despite all of the “TikTok brought me here” comments spamming trending YouTube music videos. Top comments don't necessarily translate to top consumption numbers.

Major factors for the limited relationship between these two variables may include the drastically larger size of the YouTube ecosystem (at 2.5 billion worldwide, YouTube features 5x the active users as Spotify), as well as the diversity of well-established territories and cultural differences across that user base. In YouTube world, there are numerous “frontlines” and apps outside of TikTok that draw similar attention. As an example, we noted earlier how India, one of the biggest drivers of YouTube consumption, banned TikTok in 2020.

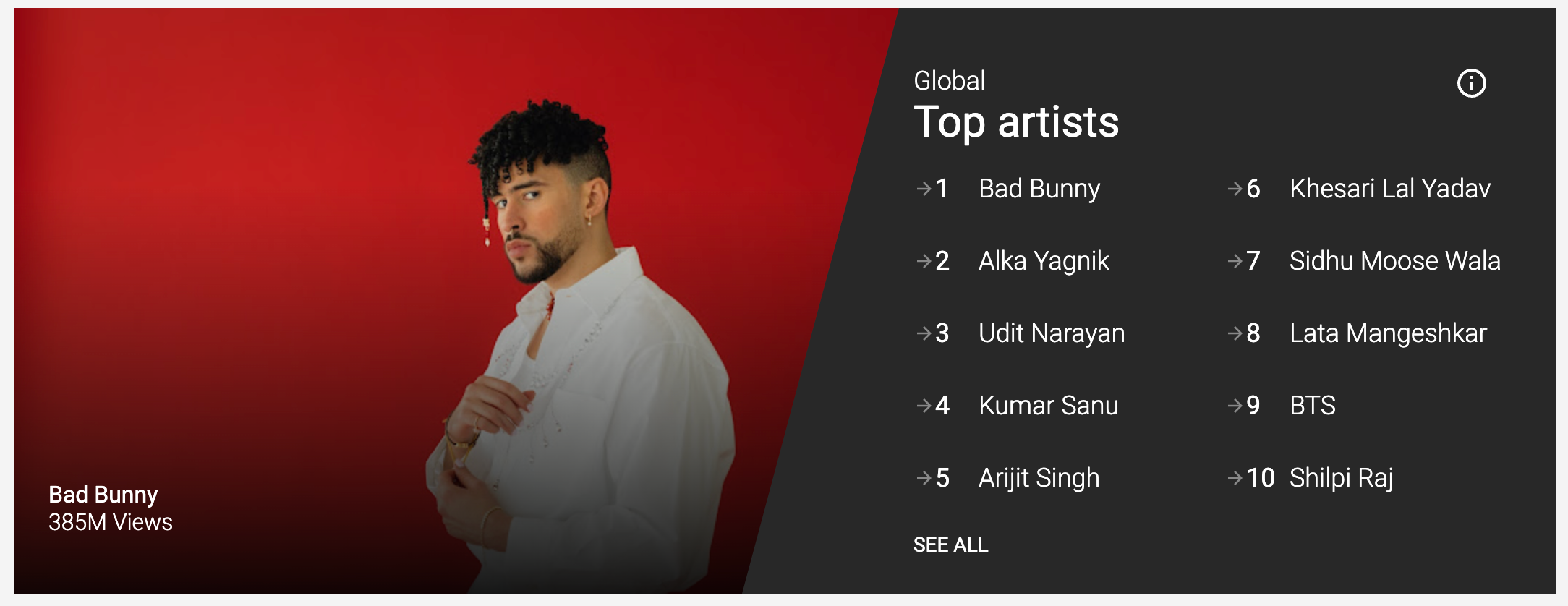

Take a look at YouTube’s top artists at any given time (see below screenshot of YouTube's top global artists in July 2022): No Ariana Grandes, but plenty of Asian and Latin artists. That's the reality of global YouTube.

While it might not be everyone’s goal to land on the Spotify and YouTube charts (and judging by the market consolidation happening on those charts, it’s probably a lost cause anyway), it is clear that there is a high overlap between what gets Shazam’d and TikTok’d and what ends up doing well on streaming platforms. This methodology doesn't even account for the many tracks that have done remarkably well on Spotify or YouTube, but didn't necessarily chart.

So, if we 1) not only expand our definition of frontline to include tracks released within the past five years but also 2) scan for digital signals of attention, i.e., TikTok and Shazam activity, to ensure we’re capturing any track (potentially regardless of release date) that’s popping off at any given moment, then we can start to make smarter decisions about how to market all music in the attention era.

The confluence of time, attention, and popularity

Now that we’ve established both the need for expanding our definitions of frontline and catalog and also the importance of focusing our attention on what’s capturing everyone else’s attention, it’s time to synthesize the two: Can we reconcile a time-based system with an attention-based system?

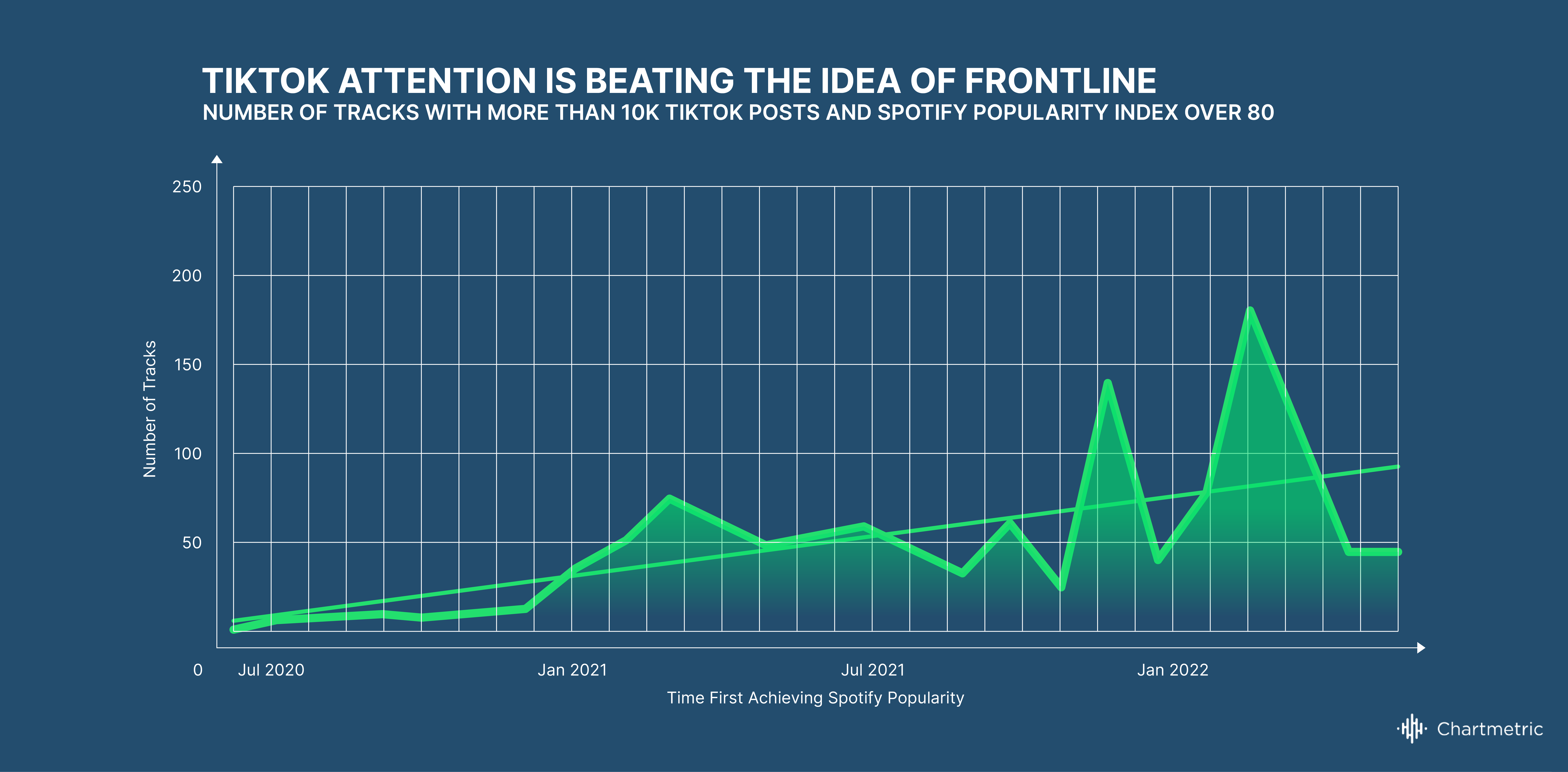

To answer this question, we again looked at tracks with considerable traction on TikTok but instead grouped them by the month (from 2020 to 2022) they first reached a Spotify Popularity level of at least 80 (out of 100) in order to determine how TikTok attention improved the growth of tracks on Spotify over time. This chart represents an attention-driven, market-focused attitude.

Beginning in summer 2020 (see second chart above), the result was a positive trendline in unique tracks from summer 2020 (<10 unique tracks per month) to the spring of this year (170+ unique tracks in March 2022). With a peak in tracks first achieving their Spotify popularity in December 2021 and an even higher peak already in March 2022 (remember, we’re only six months in), TikTok seems to be providing more top hits on Spotify as time progresses.

Conversely, the first chart (representing an internally-focused, release date attitude) shows the same kind of tracks with TikTok success showing a sharp decrease, when organized according to release year. Tracks released in 2020 (11.2K tracks) with TikTok success decreased to 2.1K tracks so far in H1 2022 (projected to 4.2K, still significantly lower).

The notably low count of tracks that achieved their Spotify popularity in 2020 suggests the diversity of tracks with significant TikTok activity in 2020 actually leveled out popularity, distributing a relatively fixed amount of attention amongst a greater population of music content. That would align with the aforementioned idea that big music companies started to consolidate the market power of their tracks on TikTok post-2020, focusing music consumer attention on a less diverse pool of tracks, and driving up the popularity of those tracks as a result.

The commercialization of a platform: same as it ever was

In 2005, the early days of YouTube were full of naiveté: brave, wacky souls speaking to camera about anything, creating the platform’s first form of social video content, the vlog. As YouTube’s active user base grew and these creative pioneers unexpectedly grew famous, industry picked up on the opportunities for advertising revenue and talent management. Very soon, the platform’s incentives changed from creativity to commercialization, and the timeless tug of war between art and commerce locked horns again. It remapped who and how they used the platform: Creators began uploading videos with the intention of becoming stars, guided by an unending stream of YouTube optimization advice to help them maximize their watch time and ad revenue.

Where does this leave TikTok? Our data seem to tell the story of an equally global platform in the throes of transition from innocent dance memes to influencer deals. We started this report with the objective of redefining — or at the very least, challenging — the traditionally held notions, in many countries, of frontline and catalog in the music industry. And while the data seem to indicate that an expanded time window for frontline seems to be in order, it’s worth remembering that this could change at any moment.

With recent news of the United States government challenging the use of TikTok domestically, it's not outside the realm of possibility the US may follow India into a scramble for new attention drivers for music discovery. Different platforms could come along and once again upend our expectations of what new and old means, again redefining our definitions of "frontline" and "catalog". Arguably, attention will continue to be commoditized, whether on TikTok, on Shazam, or on a platform that nobody has yet heard about. If we pay attention to the digital signals that indicate where audiences are focusing their attention, then time-based distinctions of where to allocate marketing resources become less important and music teams can move more nimbly by always staying ahead of the curve.

[Note on methodology: the Chartmetric database covers a large part of the Spotify, YouTube, and TikTok ecosystems, however it is not comprehensive. It is focused on the music that is most commercially relevant to our users.]

Thanks for reading Chartmetric's 6MO report.

Don't forget to join us at 11:30 a.m. ET on Wednesday, Aug. 3, for our special Off the Charts livestream, where we'll be discussing the whole report and answering all of your questions.

Questions? Comments? Reach out to us at [email protected] or on social media @chartmetric.

Contribuyentes

Senior Product Manager

Jason JovenManager, Content, Marketing, and Insights

Rutger Ansley RosenborgAnalista de Datos

Shashank ChaudharyGerente de Desarrollo de Negocios

Michelle YuenCoordinadora de Marketing Digital

Sarah Kloboves¿Listo para empezar?

Crea una cuenta al instante y comienza a obtener información sobre tus artistas, nuevas oportunidades para crecer y descubrir la próxima gran sensación.

Comienza ahora